Drivers of Behavior: SCARF

Learn more about the forces behind behaviors with David Brock’s SCARF to deepen your understanding and adjust your approach.

SCARF is a theory introduced in 2008 by David Rock, in his paper "SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating With and Influencing Others" which suggests five domains that impact behavior. Dr. Rock presents SCARF as a means to collaborate with and influence others.

Additionally, understanding the drivers of behavior can help to build understanding and empathy toward your own reactions as well as the reactions of others.

Rock cites two themes from social neuroscience in creating SCARF. The first is from Dr. Evian Gordon “much of our motivation driving social behavior is governed by an overarching organizing principle of minimizing threat and maximizing reward.”

The second is from Eisenberger and Lieberman sharing that “several domains of social experience draw upon the same brain networks to maximize reward and minimize threat as the brain networks used for primary survival needs.”

From this Rock presents five domains of human social experience:

Status- the relative importance to others

Certainty- being able to predict the future

Autonomy- a sense of control

Relatedness- a sense of safety with others (belonging)

Fairness- a perception of fair-exchanges

Status

Our relative importance to others helps us define our place in the social hierarchy. Reactions to a sense of status being threatened have been studied in everything from being removed from a project or demoted, to receiving unsolicited advice and a suggestion that someone is ineffective in a task. To reduce the sense of threat to status, leaders should allow for self-assessment and conversation and critique being driven by the individual.

A status reward is more obvious in the organization from promotion to recognition and opportunity.

Certainty

The need for certainty is based on the brain’s reliance on pattern recognition. Inconsistencies in behavior or withholding information can trigger a sense of uncertainty.

Creating a sense of certainty is based on creating reliable patterns. Aligning on expectations and goals and then being able to meet those expectations drives patterns of certainty. Telling someone what to expect or what you are going to do and then following through triggers certainty.

Tools to set expectations, deliver feedback, manage performance and even present information are built to increase certainty and predictability.

Autonomy

Autonomy or control, even the perception of control, can create a feeling of reward. A lack of agency or ability to influence others on the other hand can cause a strong sense of threat.

Teams increase certainty, status, and relatedness often offsetting some of our need for autonomy in favor of team collaboration.

Providing opportunities for self-direction, autonomy over workspace and workflows, and clear space to be creative and make decisions can add to a sense of autonomy, especially when total autonomy isn’t possible.

Relatedness

Relatedness is similar to feeling a sense of belonging or social safety and trust. Feeling safe in a group. Strangers or a lack of alignment or shared values with a group can trigger a feeling of threat to our sense of relatedness.

Creating opportunities to connect and get to know each other, to find common ground, especially on distributed and diverse teams is very important to support relatedness.

The social anxiety around networking events, especially regarding networking with new people stems from a feeling of a threat to our sense of relatedness. Consider how to drive safe connections through mentorship or buddy systems and small groups.

Fairness

Fairness is pretty clear– a perception of fairness increases our perception of reward and anything seemingly unfair triggers a sense of threat.

Transparent, clear communication and expectations help to reduce the threat around fairness. Self-direction can also support fairness.

A perceived threat or opportunity for reward within these five domains impacts how people behave or respond to situations.

Managers and leaders should keep these in mind to better understand their own as well as their employees’ reactions to help them consider the best strategy to approach different situations.

Sources

Rock, D. (2008). SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating With & Influencing Others. NeuroLeadership Journal, (1) 44-52.

Gordon, E. (2000). Integrative Neuroscience: Bringing together biological, psychological and clinical models of the human brain. Singapore: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290-292.

Talent Management Is a Cycle Not a Timeline

Talent management occurs in recurring patterns and cycles. Learn more about talent lifecycles to understand how to build more strategic talent management.

Successful companies are built by successful teams and people. To successfully manage and lead teams of people, it is important to understand all of the various elements in a talent lifecycle.

The first is to think of the company’s relationship with employees or any team member and your relationship as a manager or leader with your team members as a lifecycle, something that is cyclical and not a linear timeline.

Traditionally, you may think of employment as starting when you hire, the middle is when you are managing and the end at termination– either voluntary or involuntary.

This model is too simple and does not account for the multifaceted realities of the relationships between the company and its talent.

In reality, talent management begins before you hire and continues long after termination, it is ongoing. Organizations impact the community around them. Your potential, future, current, and former employees are in that community. The community interacts with your company as customers, consumers, followers, observers, employees, or stakeholders.

A formal employment relationship happens when the timing is right. The employee is interested in work and the company is looking to hire. But strategically managing talent or building a mutually beneficial relationship with your community of potential and former employees is always happening. When active employment ends, those employees stay in your talent lifecycle as former employees and potential next hires, continuing to interact with your broader talent pool and community.

Shiting from thinking about the talent lifecycle as linear to circular can help managers and leaders think differently about how they and their organization at large interact with both their current and former employees, contractors, and any other stakeholders. Leaders and managers move past the classic power dynamic - you are the employer and you have jobs people want so they can get paid. Instead, consider the framing, your organization is a player in a broader lifecycle and community, competing for the best talent. How you treat stakeholders of the organization in a variety of situations can have a significant impact on how you are perceived as an employer.

The remainder of this article defines the basic functions of talent management. Keep in mind, that these functions exist in a never-ending cycle, not on a linear timeline.

Elements of Talent Management

Community Engagement

This is how you or your company engages with your stakeholders aka your community at large. Your community and the stakeholder groups in it– your customers, suppliers, followers, observers, neighbors, etc. may be the potential talent to eventually work for your organization.

Your overall community is likely to be diverse in background, identity, age, ethnicity, and race.

When you see companies investing in school programs, corporate social responsibility, volunteering, or community events, etc., it is community engagement and an investment in their talent lifecycle.

Talent Acquisition

Talent acquisition is any action taken with the direct or indirect intention of attracting and hiring talent. This includes but is not limited to observing a potential need to hire, meeting potential candidates, posting a job listing, interviewing, networking with candidates, and other formal recruiting and hiring processes.

A traditional talent acquisition timeline often looks like this:

Identifying a need to hire

Establishing a hiring strategy

Posting a job listing for candidates to apply

Reviewing applications

Scheudling phone screens

Conduct interviews and maybe technical assessments

Reviewing with the hiring team

Conducting reference and background checks

Extending an offer

Onboarding

This type of traditional talent acquisition arc is what we most often see as the obvious action to acquire talent. Less obvious actions to acquire talent can look like engaging on Linkedin, networking, creating positions for amazing talent, hiring and promoting from within, hosting an event, hiring through referrals, etc. Talent acquisition is an iterative process happening all throughout the talent lifecycle.

Learning and Development

Learning and development can mean different things to different organizations, but often includes everything from onboarding and ramping up talent into new positions, to upskilling, reskilling, compliance training, and manager and leadership development. This could also include any mentorship, coaching, pairing, or peer-to-peer development opportunities.

Formal learning and development is often facilitated through the organization. Informal learning can occur when a manager assigns a project that helps a team member learn a new skill set when employees are challenged to hit steeper goals when a lunch chat turns into a lunch and learn about someone’s hobby, when an informal employee resource group forms, or any sharing of new information, tools, skills, or insights between team members.

Learning and development can be driven from the ground up, from employee interests or needs, or top-down with leaders requiring new education.

Like all other elements of talent management, learning and development is ever-evolving.

Performance Management

Performance management is traditionally thought of as tracking goals and progress, discussing feedback in formal performance reviews, and creating performance improvement plans for anyone missing expectations.

In reality, performance management is any of the direction, administration, supervision, or organization of team members’ work to impact their output and results.

Elements of performance management are related to compliance, regulation, and tracking– this is where you may see formal reviews or processes. Standardization can also be important for equity and fairness. The process may also be required for scale and alignment as well as to help ensure less HR debt as you grow.

In reality, any time you are observing, discussing, or directing someone’s work to achieve specific results you are managing performance.

Offboarding

Offboarding may look like the formal termination, dismissal, or resignation; the exit interview and any other wrap-up required.

Offboarding like any other element in the talent lifecycle can extend much further. For example, when the relationship ends, there could be space for consistent alumni engagement to create advocates and champions in your broader talent lifecycle community.

Sources

This post is a little different than others and is not based on a specific academic tool or framework but rather on experience as HR professionals and coaches working with a broad range of organizations, managers, and leaders and learning all of the possibilities associated with the talent lifecycle to achieve success.

Executive Coaching

With Talent Praxis, coaching is a partnership, where the coach partners with the coachee through a question-based creative process to find inspired solutions. The coach respects and believes in the coachee's expertise and acts as a partner to help unlock potential.

Praxis is the gap between theory and practice. Talent Praxis focuses on helping leaders turn their ideas into actions, ultimately developing an ongoing strategic practice to achieve their goals.

The Talent Praxis Process: Three Steps to Strategic Leadership

Clarify Your Vision

Define clear leadership goals and identify the strategic focuses that will drive success, alignment, and team performance across the organization.

Discover & Grow

Leverage proven frameworks, expert insights, and powerful questioning to spark reflection, deepen awareness, and experiment with growth strategies.

Craft Your Strategy

Identify essential leadership behaviors, develop actionable plans, and implement feedback loops to drive impactful, sustainable results.

What is Coaching?

With Talent Praxis, coaching is a partnership, where the coach partners with the coachee through a question-based creative process to find inspired solutions. The coach respects and believes in the coachee's expertise and acts as a partner to help unlock potential.

Talent Praxis utilizes coaching for strategic skills in leadership where there is no clear solution. In these situations, options are endless for any challenge or opportunity based on the leader's skills and needs, the skills and needs of the audience, and the unique needs of the organization.

The most common leadership topics are:

Setting and achieving impactful goals

Managing your team for high-performance

Nurturing strong relationships

Working and leading strategically

What Can You Expect in Coaching?

Coaching is a partnership based on creative questions and observations to find inspired solutions.

Coaching is unlike training, advisement, or consulting in that the coach is not there to give you advice or tell you specific next steps but rather to ask questions and create a space where you tap into greater awareness and determine the best approach to achieve your goals.

You can expect your coach to look at you as a partner in setting a valuable coaching focus, building your plan for coaching, and determining topics on upcoming calls. Expect questions like:

What are you hoping to get out of coaching?

What would be a valuable focus for coaching?

What is on your mind for today’s call? What do you want to focus on today?

Where’s the best place to start? Where should we go from here?

Coaching is also unlike therapy because coaching is more focused on progress and looking toward the future. Coaching is also not diagnostic. There is not one way to be a great leader, so your coach is not there to diagnose your leadership capabilities but rather to inspire and empower you to explore them.

You can expect your coach to share observations for discussion, ask you what you are observing from things you share, and ask you thought-provoking questions such as:

How is this important to you?

If you achieve this what becomes possible?

If you remove barriers what can you learn?

Looking forward to the moment you achieve your goal, what is present?

Through our intake process, reviewing guides on the most common leadership topics, and partnering with your coach you can set a valuable focus for coaching and create a strategic plan to achieve your goals.

The Coaching Process

Introductory call to align on expectations for coaching and build the relationship.

Partner with your coach to build a custom coaching focus and plan based on your goals and needs.

Regular coaching calls directed by your goals and needs:

Conversations are designed to evoke awareness through powerful questioning, silence, metaphor, or analogy.

Cultivate learning and growth by designing goals, actions, and accountability.

Utilize Talent Praxis resources, worksheets, and coaching frameworks based on key management and leadership tools.

Reflect on progress and observe results, consider:

What awareness have you gained from coaching?

What changes have you made or what actions have you taken?

What have been the results of those changes?

How has this allowed you to make progress toward your goals?

The Coaching Structure

The coaching structure includes establishing an overall coaching plan and goals for the coaching relationship as a whole and desired outcomes or takeaways for each individual coaching session.

This is directed by the coachee’s goals and needs from coaching. Some coachees may prefer to create a detailed agreement that outlines a specific duration, goal, success criteria for the goal, and topics for each call.

Other coachees may discuss more of a coaching focus or high-level goal they are working towards and discuss topics for individual calls in real time depending on their present context or needs.

On either end of the spectrum as the coachee, you can always adjust direction, needs, or success metrics for a given call as needed. You can also pause to reflect on your goals for coaching and the value of coaching. Your coach is there to partner with you and customize the experience to your needs.

The Coaching Call

Whether you have partnered with your coach to follow a specific structure and plan or are moving more fluidly towards your goal for coaching each call is an opportunity to reflect and focus on what is important to you.

Your coach will act as your partner and guide you through these general areas:

General check-in

Reflection on the previous actions or takeaways

Setting a topic for the current call

Partnering through the creative coaching process: powerful questions, active listening, observations, silence, metaphor, analogy, and collaboration

Discussing learning and takeaways

Designing goals, actions, and accountability

A coaching call is a unique experience. Expect reflective and introspective questions designed to evoke awareness and allow you to tap into your own expertise, creativity, and insights.

Examples of partnership questions:

“What would you like to discuss on our call today?”

“What would a successful outcome look like?”

“Where’s the best place to start?”

“What has been most impactful so far?”

“Where should we go from here?”

“What are your options?”

“What do you want to take away from this?”

“What do you want to do differently?”

“How will you hold yourself accountable?”

“How will you know if you are successful?”

Examples of questions to increase awareness:

“How is this important to you?”

“Imagine as if you had everything you needed, what happens next?”

“How would you advise yourself in this situation?”

“Where have you made up your mind and where are you still exploring?”

“What becomes possible?”

“Who do you become?”

“What do you observe in reflecting on what you shared?”

“Imagine you are in the future, what would you tell yourself now?”

“Think as if you are your biggest fan, what would you want yourself to know?”

“What are you trying to achieve?”

The Coach’s Role

Your coach is there as a partner. Your coach believes in your capability and expertise and works with you to set goals for coaching calls, evoke awareness, and create next steps and accountability.

Your coach is certified and committed to following the International Coaching Federation's ethics and core competencies. The Talent Praxis coaching definition, process, and structure are also founded in the ICF coaching ethics and core competencies.

Your coach works to stay present, open, and flexible on calls. Practicing curiosity, the power of silence, and seeking to understand you and your needs.

Your coach is also there to challenge you, present observations, and ask questions that allow you to expand your thinking.

Your Role in Coaching

Similar to your coach your main role is to act as a partner. As a partner, you share information with your coach to help them customize the coaching process and ensure it is value-adding. You openly share your observations, needs, what is helpful, and what may be even more helpful.

To get the most out of coaching practice self-reflection by approaching coaching questions with curiosity, honesty, and flexibility.

The format of coaching may be new and unfamiliar. Give yourself time and space to learn a new format for learning and growth.

Challenge yourself to spend time in between calls to practice any takeaways you committed to, reflect on the conversation and awareness, and brainstorm potential topics that are important to you for the following call.

You are committing to showing up prepared and present during calls. Prep for a coaching call may only take 5-10 minutes. Ideally, the time commitment or “homework” in between calls does not take any extra time; instead, you are committing to practicing your day-to-day work differently by applying your new awareness and drawing awareness to the results.

Intrinsic Motivation and Engagement

Explore the key drivers of motivation and engagement to learn more about what inspires people to work and stay committed.

Intrinsic motivation and engagement are keys to building sustainably high-performing teams.

Intrinsic motivation is often mistaken for extrinsic motivation – a drive that comes from externally motivating factors such as compensation or rewards, and engagement is often mistaken for hours worked.

In reality, intrinsic motivation and engagement are the internal, emotional drivers – the “why” behind an individual committing to their work and employer.

“Intrinsic motivation is the individual’s desire to perform the task for its own sake.”

“Gallup defines employee engagement as the involvement and enthusiasm of employees in their work and workplace.”

More on Intrinsic motivation

Intrinsic motivation has three key drivers (or pillars) originally from the Cognitive Evaluation Theory of Motivation and more recently popularized by Daniel Pink.

Mastery: information to increase competence

Autonomy: self-determination

Purpose: connection

Extrinsic motivation is defined as a contingent reward. Benabou and Tirole report that extrinsic motivators “have a limited impact on current performance, and reduce the agent’s motivation to undertake similar tasks in the future.” For sustained performance managers and leaders should focus on the pillars of intrinsic motivation.

Mastery

Information, competency, and anything that allows one to gain mastery and achieve success is a powerful and dynamic motivator.

Feedback, whether positive or constructive is intrinsically motivating because it is information that one can utilize to understand how to build mastery and be successful.

Training, development, growth, and opportunities to learn are all often coined as intrinsic motivators because they help to increase mastery.

Transparency, open dialogue, and information sharing are often associated with successful leadership because doing this also helps to increase mastery.

Autonomy

Autonomy or self-determination is an intrinsic motivator because it gives an individual control, this is based on the Self-Determination Theory.

Autonomy comes up in successful change management – when someone is a part of the decision to make a change, the change is more likely to be successful.

This need for control can also drive success and accountability. If the individual feels they have a say in the decision-making process, outcomes, and deadlines, they are more likely to be bought in and motivated to get the work done.

Autonomy is not an all-or-none facet. As a manager and leader, draw awareness to how many decisions you control and where your team members have opportunities to be autonomous and take part in decision-making.

Purpose

This is connection, it is the “why” things matter and how they interrelate.

Compensation can be an intrinsic motivator when it connects values between work and personal life. ”I work because I am trying to buy a house and need a big bonus this year to get my first family home.” The motivator is not income, the intrinsic motivator is the value of family or support.

The connection is often value-based. When a company or team's values connect to someone’s personal values it drives purpose to do the work.

Purpose or connection, in its simplest form, answers the question “why?” Why someone should work, complete a project, show up to meetings on time, etc. The why drives motivation. This is why great leaders lead with a why, with a purpose.

More on Engagement

Engagement or the emotional connection to work is not measured by how early someone shows up, how many hours they work, or if they meet expectations. Engagement is measured by an emotional connection.

Culture Amp, one of the leading employee engagement tools, measures engagement by:

Pride in one’s company

Willingness to recommend the company as a great place to work

How often they look for another job

If they see themself working there in two years

Whether the company motivates them to go above and beyond

There are plenty of external factors that impact someone’s ability to get to work early, work long hours, or show up 100% every day. An employee's true engagement goes beyond this. Think about aggregate engagement over time.

It is the employees who align with the company’s mission, product, service, and customers, that reliably deliver solid work over time. Think of the employees who check in with new hires without asking and regularly engage cross-department, these are the employees who are truly engaged. Engaged employees are the company’s champions more than workhorses.

Read further

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999, December). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effect of extrinsic ... Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12712628_A_Meta-Analytic_Review_of_Experiments_Examining_the_Effect_of_Extrinsic_Rewards_on_Intrinsic_Motivation

Pink, D. (2009). The Puzzle of Motivation. Dan Pink: The puzzle of motivation | TED Talk. https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_on_motivation?referrer=playlist-the_most_popular_talks_of_all

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2003, January). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Princeton University. https://www.princeton.edu/~rbenabou/papers/RES2003.pdf

Culture Amp. (n.d.). Guide to defining employee engagement - culture AMP Support Guide. Engagement + Experience. https://support.cultureamp.com/hc/en-us/articles/204539759-Guide-to-defining-employee-engagement

Sinek, S. (2022). Simon Sinek: How great leaders inspire action. Ted Talk. https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action?language=en.

Leadership Theories and Defining Your Values

Learn the prevailing theories of what motivates leaders, consider where you relate, and define your own values for leadership.

Northouse defines leadership as a process of influencing others to achieve common goals. It is not a trait or characteristic but rather a transactional event that occurs between leaders and those they lead.

Common leadership theories strive to define the values and motivators of great leaders. Often based on case studies, these are not identities or one-sized fits all blueprints for leadership but rather aggregate trends found by researchers in leadership.

Your leadership style and motivators are unique to you, how you work, and your values. You can learn from prevailing leadership theories and take the time to understand yourself and who you are as a leader.

Leadership Theories

When reading the theories below, resist the urge to relate to one and move on. Instead, look at each with curiosity and an open mind.

What can you learn from these, what do you connect with, what surprises you, and what may be the pros and cons of each?

“Authenticity has become the gold standard for leadership” —Harvard Business Review, January 2015.

Bill George first popularized the Authentic Leader as a leader who:

Understands their purpose

Practices solid values

Leads with heart

Establishes connected relationships

Demonstrates self-discipline

“The servant-leader is servant first… It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first.” -Robert K. Greenleaf

Greenleaf shares that there are leader-first and servant-first leaders, but both are extremes. The servant leader focuses on the growth of others and their communities while a leader-first leadership persona focuses on accumulating and exercising power. The gray middle area is those who focus on others’ growth while strategically practicing a directive leadership role.

Servant leadership has mostly been portrayed by the metaphor of the pyramid. Where in the leader-first, the leader is at the top of the pyramid and those they lead is at the bottom, in servant-first leadership, the pyramid is flipped with the people they lead on top and the tip, aka the leader, at the bottom.

Transformational Leader

“Leaders and followers help each other to advance to a higher level of morale and motivation.”

-James MacGregor Burns 1978

Bernard Bass expands on the definition of a transformational leader in his book published in 1985. He measures leadership by a leader’s influence over their followers. Citing trust, admiration, loyalty, and respect as measures of influence. Transformational leaders develop this influence through an inspiring:

Mission

Vision

Identity

“Adaptive Leadership is the practice of mobilizing people to tackle tough challenges and thrive.” -Heifetz 2009

Adaptive leadership first came about from Ronald Heifetz in Leadership without the Answers in 1994.

An adaptive leader:

Encourages people to change, grow and learn

Focuses the attention of others

Mobilizes, motivates and organizes followers

Helps others explore and change their values to adapt

You as a Leader

Your Story

Think about your life experiences and the defining moments that have shaped you into the person and leader you are. The moments that have shaped your beliefs, opinions, and decisions.

If that feels completely overwhelming start by looking over your resume or LinkedIn. Where have you worked, what were the organizations like, what were your roles, and what were your managers like? What impact have these variables had on the way you are as a leader?

Where did you grow up? What was your family like? Where did you go to school? What did you study? What impact have these variables had on the way you are as a leader?

Then try to find the common thread that ties this together.

Your Workstyle

Next, think about your work style. What is it like working with you and for you? Ask some coworkers and see what they say. Think about trends and patterns- do you show up early to meetings, are you outspoken, are you organized, are you creative, etc? What are you like as a manager?

Your Strengths

For strengths consider:

Your technical skills and expertise

Your behavioral strengths, skills that cannot be learned from a course as much as through experience in how you work with others

Your personality traits, things that make you unique

If you are stuck, look for an old cover letter, interview prep, or performance review. Consider the feedback you have received throughout your career, for example, what are you often complimented on? Consider the things that come easily to you but don’t seem as easy to others, or ask a coworker, or a good friend to tell you what they think you are good at.

Your Values

Your values are the things most important to you. They may evolve over time. There are a few ways to define values:

Think about the most meaningful and challenging points in your life. In the most meaningful, what was present, what was important to you? In the most challenging, what was missing, and how was that important?

Do a raw brainstorm– list out all of the words that quickly come to your mind. Bucket them by similarity. Dig into each bucket to find the overarching value by asking- what is important, and what matters most to you?

Look at existing lists of values and grab anything that stands out to you. Like this one.

Now narrow this down to something you can remember. This is likely at most 5-7 values. To do that, try to find the overarching themes around what is most important to you by defining the values, and looking for overlaps or commonalities. Ask yourself “why”– why does this value matter to me? Keep asking why until you hit a wall and find yourself saying the same things.

Combine your story, workstyle, strengths, and values– what does this say about your leadership style and how you want to lead?

Read further

George, Bill (William W.). Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value. San Francisco :Jossey-Bass, 2003.

What is servant leadership? Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.greenleaf.org/what-is-servant-leadership/

Burns, J.M, (1978), Leadership, N.Y, Harper and Row.

Bass, B. M, (1985), Leadership and Performance, N.Y. Free Press.

Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership. Harvard Business Review Press.

Northouse, P. G. (2019). Leadership: theory and practice. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, SAGE Publications.

Delegate Effectively

Two key frameworks help leaders determine when and how to delegate by balancing delegation, monitoring, and doing it yourself.

Two key frameworks help leaders determine when and how to delegate by balancing delegation, monitoring, and doing it yourself.

Tool Summary

To focus your time on the most valuable work, you need to prioritize and delegate. The Consequence-Conviction Matrix presented by Keith Rabois in Sam Altman’s ‘How to Start a Startup’ lecture series at Stanford helps to asses what to delegate without abdication or micromanagement based on conviction and consequence.

The first dimension is conviction or the strength of your opinions or beliefs about something. The second dimension is the level of consequence or the risks involved in someone else doing the work. These two dimensions help to determine what tasks should be delegated.

The Consequence-Conviction Matrix stems from Task-Relevant Maturity (TRM) model coined by Andy Grove in his book High Output Management. TRM compares the importance and urgency of a task to someone’s maturity or skill to do the task.

Highly important or urgent tasks can be delegated to skilled employees and monitored or should be done yourself. While tasks with low urgency and importance can be delegated to skilled employees or delegated and monitored to non-skilled employees.

Combined these two help to determine when and how to delegate work.

How to Apply

Ask yourself the following three questions when determining when and how to delegate:

Step 1 - What is your level of conviction about a decision (low or high)?

How strongly do you believe you know the right way to do the work?

How accepting are you of various paths or methods to complete the work?

Step 2 - What is the level of consequence in how the work is executed or what is the degree of risk (low or high)?

What is the impact if a mistake is made?

How risky or important is the work and desired result?

Step 3 - What is the skill and will of your team members who could complete the work (low or high)?

What is their skill level in the task at hand? What is their potential to be successful?

How bought in are they to complete the work?

After answering these questions you need to determine the level at which you want to:

Delegate the work to others vs. do it yourself

Monitor progress vs. delegate it fully

The lower the skill level the more you need to monitor or do it yourself. In low conviction/ risk moments, you can monitor or developmentally delegate and in high conviction/ risks moments, you do it yourself.

The higher the skill level the more you need to delegate fully or delegate and monitor. Here you delegate fully when there is low conviction/ risk.

When there is high conviction, risk, or importance you need to strike a delicate balance between delegate and monitor. This is a challenging space because you want to delegate fully to highly skilled team members so they feel empowered. Ideally, the skill of your team members lowers the risk.

If your conviction, the risk, or the importance outweighs the skill of your team members- consider if the skill is low enough you should do it yourself. If not, you will want to utilize monitoring and reporting, enough that you are confident the most important work is done well, but not so much that you disempower your team members.

Your decision is more of a scale than a binary point. Be thoughtful of the balance between the motivation and engagement of your team members with your need to monitor, report, or do it yourself.

Measuring Results

The goal of proper delegation is for the right people to do the right work to make the highest impact. If done correctly:

You should have time to focus on the most important work

Your skilled team members should feel trusted and autonomous

Less skilled team members should have opportunities to develop and grow their skills

Your conviction and the consequences of work should be clearly communicated

There is safe space for risks and mistakes

Monitoring and reporting should be valuable tools

Sources

Grove, A. S. (1983). High output management. Chapters 3, 4, 9, 11, 13, 14, Souvenir Press.

Rabois, K. (n.d.). How to Operate. Sam Altman, How to Start a Startup. Stanford University. Retrieved from http://startupclass.samaltman.com/courses/lec14/.

Listening for Understanding: 3 Key Listening Tools

Practice active listening, levels of listening, and strategic questions as tools for a deeper understanding of how to build greater awareness, trust, and alignment.

Practice active listening, levels of listening, and strategic questions as tools for a deeper understanding of how to build greater awareness, trust, and alignment.

Tools Summary

Active Listening

Active listening begins with the foundation of respecting the speaker, and a desire to understand their perspective and viewpoint. In 1957, Carl Rogers and Richard Farson coined the term active listening and it later was popularized by Gordon Model and the P.E.T. program.

It requires the listener to give their distraction-free attention and focus. The active listener is looking for both the content and the context of the message. This action conveys to the speaker a level of respect and sincere interest in understanding.

Levels of Listening

Start to enhance your listening skills by adjusting your level of listening for any given situation. Dr. C. Otto Scharmer, a senior lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, presents 4 levels of listening:

Downloading, listening from habits. Reconfirming what you already know – confirming your opinions and judgments.

“What do I hear or assume?”

2. Factual Listening, listening from the outside. Listening with an open mind, suspending habits of judgment. Looking for information, data, and any disconnections.

“What is the data or information? What are the objective facts?”

3. Empathic Listening, listening from within. Listening with an open heart to see the situation through the eyes of another. Tuning into another person’s view to gain an emotional connection.

“What is the speaker’s perspective?”

4. Generative Listening, listening from the source. You listen for the highest future possibility to show up while holding a space for something new to be born. This connects to see who you want to be.

“What becomes possible?”

Strategic Open Questions

The type of questions you ask impacts the response you receive. Asking more strategic open questions can increase your awareness and allow you to better practice active listening.

Open questions start a conversation and create a learning opportunity. Closed questions limit responses and awareness. Open questions embrace the other person with curiosity and desire to understand, furthering your practice of active listening.

How to Apply

Active Listening

To practice active listening start by considering your intentions and mindset. Plan ahead to take the viewpoint of the speaker, and reserve judgment. Seek to understand.

Practice awareness of the content and the feeling behind it. You could do this by taking notes during a conversation, discussing your observations live to find shared understanding, or debriefing on what you learned after.

If you think you observe a feeling, confirm and validate it. “How are you feeling?” “Thank you for telling me you feel frustrated.”

After listening, instead of moving on to another point, restate what you hear for clarification and to ensure understanding. “I think I am hearing… is that correct?”

Levels of Listening:

Supercharge your listening by navigating through the 4 levels of listening:

Downloading - what did they say?

Factual - what are the facts?

Empathic - how are they feeling? How are you feeling?

Generative - what becomes possible?

Strategic Open Questions:

Consider these questions to create more impactful conversations that are directed by the other party:

Consider more open instead of yes or no questions:

Practice “What is your timeline?” vs. “Do you have a timeline for this?”

Avoid Lists:

Practice “What’s your plan?” Vs. “Do you want to go with plan A or plan B?”

Avoid presenting the solution

Practice: “What stakeholders do you want to loop in?” Vs. “Shouldn’t you check with marketing first?”

Avoid assuming emotion- never state emotion unless they do.

Practice “How are you feeling?” Vs. “Why are you frustrated?”

Example

Imagine active listening in action and consider how you can practice in your next meeting or conversation with a team member. An example of this tool in practice looks like starting the virtual project update meeting with your inbox and collaboration tools closed, and your phone on silent.

As the meeting starts, you are listening to a team member to understand what they are working on, and their perspective on the progress or roadblocks they are facing. You listen to how they are feeling about the work. Listening actively in all four levels.

Before the topic changes, you take an opportunity to ask for clarification to be sure there is alignment such as “it sounds like this project will be delayed by a week, is that correct?” The speaker has a chance to clarify or confirm before moving on.

As you two discuss this, you ask strategic questions to invite the team member to further engage in the conversation such as “what stakeholders do you want to loop in about the project changes?”

This approach creates a more productive conversation between you two where you avoid any miscommunication.

Measuring Results

Where are you experiencing increased alignment, learning new things, or achieving better results?

Notice where you recognize the context and fuller meaning of the message. Consider how this grows your connection with the other party.

Practice using more strategic questions, and observe the different responses you receive.

Practice closing your inbox/phone and any other tools that would distract you from a conversation.

Notice what the results are of conversations when you are focused, distraction-free, and listening strategically.

Sources

Rogers, C. R., & Farson , R. E. (2021, March 3). Active listening. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books/about/Active_Listening.html?id=Vz1SzgEACAAJ

Scharmer, O. C. (2015, November). The Four Levels of Listening. Threefold Consulting. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLfXpRkVZaI.

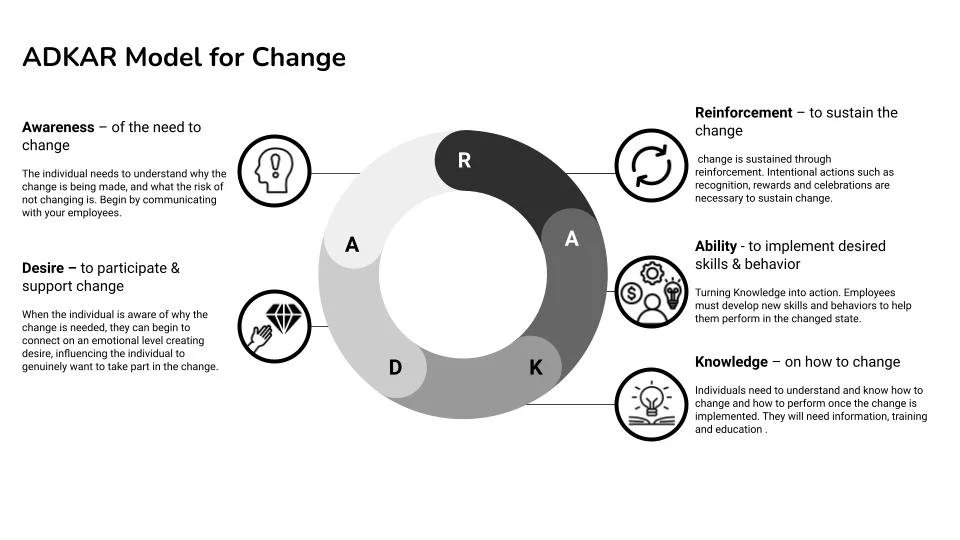

Managing through Change: ADKAR Model

As a leader, one of your key responsibilities is navigating your team through change. ADKAR is a change model leaders can use to establish a plan to help individuals move through change successfully.

As a leader, one of your key responsibilities is navigating your team through change. ADKAR is a change model leaders can use to establish a plan to help individuals move through change successfully.

Tool Summary

ADKAR model was developed by Jeff Hiatt in 1998 to show how change can only happen through individuals. The model illustrates the key concepts that influence successful change and provides actionable insights for implementing these key concepts. The word “ADKAR” is an acronym for the five outcomes individuals need to achieve for successful change: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement.

How to Apply

Awareness:

For effective change, the individual needs to understand why the change is being made, and the risk of not changing. The individual needs to be made aware of the internal and external drivers for change, the benefits of making the change, the “what’s in it for me” argument, and the nature of the change.

Helping your employees understand the “why” is a critical factor in managing and enabling change. It's not enough to just tell your employees what is about to happen. Your employees need to internalize the nature of the change and why the change needs to occur.

Tactics for effectively building Awareness include:

A change communication strategy with your employees- appropriately timed announcement, explaining what needs to occur and why on multiple occasions in multiple formats and forums, and providing opportunities for employees to ask questions and voice concerns.

Strong sponsorship, the primary sponsor of the change is visible and communicates often and effectively with employees about the why of the change.

Coaching by people managers to help team members understand what the change will mean for them in practice and in their day-to-day work. People managers face one of the toughest challenges as they will often be in charge of seeing that the change is actually implemented. For people managers to be able to do this effectively, they need to be equipped with the right information, tools, coaching, and training skills to help their team members implement the change.

Ready access to business information to increase the sense of transparency and keep building awareness on an ongoing basis.

Desire:

When the individual is aware of why the change is needed, they can begin to connect on an emotional level to how the change may benefit them. Creating desire will influence the individual to genuinely want to take part in the change.

Building desire can look like: communicating the benefits of the change, identifying the risks involved, and discussing these openly. Understanding on an emotional level why the change is needed and what the risks of not changing are will help build momentum and a sense of urgency.

Active and visible sponsorship from leadership, frequent communication, proactively addressing risks, engaging employees in the change process, and aligning incentive programs including promotion parameters or pay/bonus scales with project metrics and goals are seen as important tactics to successfully create desire.

Knowledge:

Employees need to be given the information, training, and education necessary to know how to change and how to perform effectively in the future state.

First address the current level of knowledge, capability to learn, and resources available for education and consider what is needed throughout the change.

Next, training and education programs based on the identified knowledge gap should be planned and put in place. Training and education programs can take many forms and should be tailored to take into account the unique change and circumstances, and the needs of the individuals involved.

One-on-one coaching and job aids such as reference guides are effective methods to help translate how to change into how to perform once the change is implemented.

Ability:

Ability turns knowledge into action. At this stage, the change is actively being executed. Employees' ability to develop new skills and behaviors to help them perform in the changed state is put to the test.

Balance a sense of urgency to keep up the momentum, with space and time for employees to feel safe to learn, make mistakes, and try again until new habits, skills, and behaviors are successfully formed.

Managers and change leaders are in key roles- helping to coach, providing resources and tools, and creating time for team members to be able to build these new skills and behaviors.

Support, time, and an individualized approach are considered keys to success at this stage of implementing a change. Managers must be ready and equipped with the time and resources needed to provide one-on-one coaching and feedback in a safe and supportive environment.

Reinforcement:

Change is sustained through reinforcement. This stage is often overlooked though critical to ensuring the long-term success of implementing change.

Like with habits, it takes a long time until new ways of doing things and new behaviors become the new normal. After an initial push, without consistent, ongoing reinforcement of the new behavior, it is easy to revert to old, familiar patterns.

Intentional actions such as recognition, rewards, and celebrations are necessary to sustain change. Reinforcement helps to build positive momentum.

Success feeds success. It's important to seek out wins and celebrate these, especially in the beginning when you are at the most challenging stage of implementing a change.

Other ways to reinforce the change are to use rewards and provide opportunities for employees to voice feedback by using audit and performance systems as well as ensuring accountability systems are put in place. Negative consequences can become a barrier to change. Reinforcement strategies should strive to associate success with progress. When individuals can see the impact of successes, even small progress, the desire to change is reinforced and momentum upheld.

Measuring Results

To measure results consider these questions?

How well do your employees understand and agree with the reasons and ways in which a change is to be made?

How invested in and excited are your team members about the change that needs to be made?

Do your team members feel they know how they are expected to change and perform in the future state?

How well are your employees able to perform in the changed state? Do they feel they are getting what they need to implement the change, and to build new skills and behaviors needed?

Can your employees see how the change is progressing? Do you celebrate wins? Is there a sense of momentum? Do your employees feel committed to the change?

You can survey to assess or observe what is occurring. Are you meeting your goals for the change? Are you retaining your employees throughout? If you are strategic in your change management you should see your goals play out and retain employees or observe continued engagement in the new systems.

Source

Inc., P. (2003). The PROSCI ADKAR® model. Prosci. https://www.prosci.com/methodology/adkar#:~:text=The%20model%20was%20developed%20nearly,change%20leaders%20around%20the%20world.

Intentional Prioritization: Eisenhower Matrix

Prioritize your work with the Eisenhower Matrix, originally developed by President Eisenhower to organize high-stakes issues.

Prioritize your work with the Eisenhower Matrix, originally developed by President Eisenhower to organize high-stakes issues.

Tool Summary

The Eisenhower Framework is a prioritization tool to help you understand how to use time more effectively. It is originally credited to President Eisenhower in a variety of different public speeches and was formally used as a productivity framework in Franklin Covey’s book in 1989 “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.”

The framework asks you to first categorize your work or tasks based on two aspects: importance and urgency. Then depending on how you categorize your work you will have a 4 bucket priority list and an action to take for each bucket.

How to Apply

The Eisenhower Framework can be applied effectively in a few ways. The first is to think more critically about your personal definitions of important and urgent.

What does important mean to you? Is it work or tasks tied to company goals, team goals, personal goals, or values? Rank importance for you.

What does urgent mean to you? What is your perceived deadline and what created that deadline? What will occur if you miss the deadline?

Sometimes thinking more intentionally about the importance of and urgency of work can be enough to more effectively manage your time.

The next step to applying the Eisenhower Framework is to categorize your work into 4 buckets (1) urgent and important, (2) important but not urgent, (3) urgent but not important, and (4) not urgent nor important. These are listed in priority order.

In each priority category, there are different actions. For (1) urgent and important work you need to complete it first.

Ideally, important work should never become urgent so consider: is there an external force causing a fire drill? How often do these occur? How can you block time for unanticipated urgent and important work? If it is not external, how and why did you procrastinate and how can you avoid this in the future? If something is urgent and important you will usually be forced to work reactively which can prevent you from producing the best quality results.

(2) Important but not urgent work is where you accomplish your goals or make real progress that is high impact. This is where the majority of your time should be spent. Spending the majority of your time on this bucket of work means that you can be proactive rather than reactive.

(3) Urgent work that is not important should either be rescheduled or delegated. It is time-bound but does not have a meaningful impact.

(4) Not urgent nor important work should be avoided, delegated, or time-boxed. If you have to do it, can you keep it to a manageable amount of time that still allows you to accomplish the priorities above?

Once you apply all three steps of the Eisenhower Framework you may want to consider Franklin Covey’s Big Rocks, Little Rocks. It suggests through the metaphor of a jar to be filled with big rocks, little rocks, and sand, that the best way to fill your jar, available time, is to start with the big rocks- urgent and important work, and then continue to fill your jar with the little rocks- urgent but not important work, and lastly fill the rest of your jar with sand- not important or urgent work.

When planning your week ahead- plan to set aside time for your big rocks, important work, first.

Measuring Results

When you are successfully prioritizing your work two things occur. (1) you know what your key priorities and focuses are for any day or week. You know what to spend your time on and what to say no to. If someone asks you “what are you focused on today, this week, this quarter?” you can answer that question easily.

(2) You feel in control of your time and workload. What feeling in control means to you is of course subjective. Consider what is your desired mindset and how can this tool help you get there.

Sources

“President Eisenhower used to arrange his affairs so that only the truly important and urgent matters came across his desk. He reportedly discovered that the two seldom went together. He found that the really important matters were seldom urgent, and that the most urgent matters were seldom important.” 1973 an article about “Managing a Small Business”

Covey, S., 1989. The seven habits of highly effective people. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Strategic Management: Situational Leadership

Practice Situational Leadership to strategically adjust your actions to align with the situation and associated needs.

Practice Situational Leadership to strategically adjust your actions to align with the situation and associated needs.

Tool Summary:

Situational leadership is a framework that helps you assess the situation at hand to determine how directive, supportive, or hands-off you need to be as a manager to achieve your desired results. In 1969, Blanchard and Hersey developed Situational Leadership Theory in their book Management of Organizational Behavior.

There are two steps: (1) assess your situation considering the time available, the skill, and the will of the audience (collectively referred to as performance readiness), and (2) pick the best action to take – telling, selling, supporting, or delegating.

How to Apply:

To apply Situational Leadership you need to start by building your awareness of the actions you take as a manager. You need a level of mindfulness to understand how and when you can and should adjust your actions and behaviors to accomplish your ideal outcome.

Next, consider your situation at hand from the 3 perspectives below.

Time:

How much time do you have?

How much time should you spend on the work at hand?

What is the risk or impact of this work?

Will:

What is the willingness (degree of motivation) of your audience to complete this task?

How bought in and committed are they to the work?

Skill:

What is the skill level of your team member or target audience?

How capable (based on their current skills) are they of completing the work?

Do they have the required tools, resources, or information?

Considering the time available, the skill and the will (performance readiness) of your audience consider which of the 4 situational approaches would be most likely to yield desired results and lead to success.

Directing:

Directive behavior can be considered authoritative or instructive. This approach is most effective when the situation at hand is time sensitive and your team member lacks the skills needed to execute. When a lack of skill and time means that you are unable to quickly delegate tasks, you will need to give instructions instead.

When you need things done in a certain way and the risks are too great to allow for mistakes or failure, for example in crisis situations, a directive approach may be the best way to resolve the situation quickly. Think about a high-profile client, a big account, or a compliance process – anything where the work needs to be done in a specific manner to achieve results. Usually, your approach needs to be swift and instructional.

If you find you are often using a directing approach for the same tasks, consider whether you could move to a supporting and eventually a delegating approach.

When the work is too complex to give quick instructions, it is also time to consider how you could shift to a supporting or delegating approach.

Selling:

Selling is a consensus-driven behavior. A selling approach is appropriate when your audience lacks will and skill, and you have time available. To increase will, you need buy-in. You can build buy-in by involving your audience- asking questions, brainstorming, leading collaborative conversations, pitching a new idea, or facilitating a Q&A, etc. to help you find alignment.

This is very useful when you want to solicit multiple ideas, innovate on a new solution or ensure everyone is aligned on the work.

Selling takes a lot of time and could lead to stalling from indecision. Consider the culture you need around decision-making, disagreement, and ownership. Depending on the work at hand, determine when and how long to be in selling mode.

When you find your team members are gaining in skills and you no longer need to focus on creating buy-in, you can move into a participating approach.

Supporting:

Supporting involves participation and is a collaborative behavior. You are using a supporting approach anytime you are working directly with your team and focused on their development. This may look like training, teaching, coaching, shadowing, partnering, pairing, etc.

This approach is most effective when your audience is highly willing and at least moderately skilled and you have time to participate.

As with any participation your audience needs to be fully willing, they need to be bought in on and aware of the development target, the gap between where they are now, and what it will take to get there.

If you do not have the buy-in move back to asking. Once you see that your team members have gained skill and confidence you can move to delegating or do a hybrid, developmental delegation.

Delegating:

Delegating is a hands-off behavior. This is when you empower another team member to do the work. You can and should still align on basic expectations, especially around timing and metrics of success. It is the least directive approach. How much you align on delegated work depends on how much room there is for variation. Be critical of yourself here. What details are truly important? As long as results are achieved, give your team members space to work in the way that’s best for them.

Example

Directing:

“We have a meeting with marketing tomorrow at 2p and will need the final mock-up of the new product launch by then. Can you implement all of the feedback today by 3p and email it to me, so I can review it and incorporate it into my presentation tomorrow?”

Selling:

“We have a meeting with marketing tomorrow at 2p and will need the final mock-up of the new product launch by then. How are you feeling about my feedback for the mock-up? What do you think we should change? How should we best distribute the work? What timeline makes sense here?

Supporting:

“We have a meeting with marketing tomorrow at 2p and will need the final mock-up of the new product launch by then. I booked time for us to review the feedback, finalize the mock-up, and practice the presentation together.”

Delegating:

“We have a meeting with marketing tomorrow at 2p and will need the final mock-up of the new product launch by then. Do you have everything you need to get that ready?”

Measuring Results

Ideal results from practicing situational leadership depend on your goals. Maybe you are noticing you are spending too much time on work, you are getting pushback from your team members, you want more collaborative problem-solving, your team members want development opportunities or you need to delegate more.

In any scenario, start by quantifying results today and consider how you can measure change. Measurements should both be objective and qualitative- what would change look like and what would it feel like?

This tool can be iterative and fluid at the moment. The most impactful change may be greater awareness of your actions and an ability to pivot live as you receive feedback from your audience.

Source

Blanchard, K. (2022). Create success with a situational approach to leadership. SLII® - A Situational Approach to Leadership, from https://www.kenblanchard.com/Solutions/SLII

Setting Actionable Goals: Think SMART

Use SMART, leads, and lags to define more specific and actionable goals, so your team knows how to achieve results.

Use SMART, leads, and lags to define more specific and actionable goals, so your team knows how to achieve results.

Tool Summary

SMART is a framework to help think, define and communicate work, expectations, projects, and goals more strategically. The acronym stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timebound.

How to Apply

To begin thinking SMART you need to make time to pause and reflect. Start by asking yourself these five questions:

S - What am I working on? (Specific)

M - How will I know if I am successful? (Measurable)

A - How likely am I to be successful? (Achievable)

R - How is this important? (Relevant)

T - What is my deadline? (Time-bound)

Save these five questions and use them anytime you need direction, clarity, prioritization, or alignment.

You can apply the SMART framework to your own goals and work as well as team goals and work. When you are working with others, would all of the answers to these questions be the same? Where should they differ and where should they align?

Measuring Results

To measure results, dive deeper into each category.

Specific:

Specificity, details, or definition is one of the key things that help to avoid procrastination and create alignment with others. If your work is too vague, you may find it challenging to get things done or you may find yourself misaligned or miscommunicating with others. The more specific things are defined, the easier it is to know what you are working on individually or as a group.

Measurable:

Goals should be measurable. The ability to measure progress and achievement of a goal on a defined scale helps with alignment and clarity on what a successful outcome looks like objectively. Measurement also helps with everyday tasks and expectations to mitigate procrastination. Measurement creates a clearer view of progress, impact, and priorities. To make things more measurable consider:

What are the lead measures, or inputs?

What am I doing to contribute to the success of my work?

What is my role?

What am I expecting my team members to do?

What are the lag measures, or outputs?

If I am successful what happens differently?

How will I know?

How am I reviewing if others are successful?

In either of these, you can track the objective measures you can see or the subjective measures you can feel.

If you are successfully thinking about “measurability” you have a clear definition of success, a path to get there, and know when you have made progress.

Achievable:

Your goals, work, and expectations should be achievable. If success seems unlikely, it becomes easier to procrastinate. Determining how achievable work or goals are can be subjective. You may look at the situation differently than someone else. Your abilities, personal values, and standards impact what a stretch goal and what an easy goal looks like to you. What is achievable to you, may not be as achievable to someone else. Achievable goals should be challenging enough but not too challenging. Talk to your team members and other stakeholders to define achievable success.

When considering achievability, you also need to take into account any variables and factors that impact success, are in control, and are out of control.

Relevant:

Why does the work or goal matter? When you think about relevance, you need to consider impact and importance. You should feel like what you are working on matters, will have an impact, and is worth doing. If you do not see how and why the things you are working on are relevant, the work easily becomes unmotivating and even frustrating.

Timebound:

The goals you define and the work you are doing should have deadlines to maintain a sense of urgency and to help you see the finish line. Deadlines help you maintain focus and provide guidelines to help you assess what you need to do and when you need to do it. Considering how long something should realistically take should help you quantify more realistic deadlines that hold you accountable.

Examples

Goal

“Our team will increase sales by 10% over the next quarter through each team member conducting 100 dials/day and producing 5 demos/week resulting in closing 10 deals each month to help meet the department revenue KPIs.”

S - [the specificity is in the other details]

M -

Lead: “conducting 100 dials/day”

Lag: “producing 5 demos/week”

Lag: “closing 10 deals each month”

Lag: “increase sales by 10%”

A - [this is not noted specifically, it is assumed the intended audience would agree the leads and lags are acheivable]

R - “help meet the department revenue KPIs”

T - “over the next quarter”

Expectation

“In the new collaboration project with design, I would like you to take the lead on sharing the customer perspective, sending any useful prereading before meetings, and representing the customer using learnings from your latest user research during meetings. It is important we work together with design to come up with a shared solution before the end of the month that the majority of our customers will benefit from.”

S - “In the new collaboration project with design I would like you to take the lead on sharing the customer perspective”

M -

Lead: “sending any useful prereading before meetings and representing ` the customer using learnings from your latest user research during meetings”

Lag: “shared solution… the majority of our customers will benefit from”

A - [this is not noted specifically, it is assumed the intended audience would agree the leads and lags are acheivable]

R - “It is important we work together with design to come up with a shared solution”

T - “before the end of the month”

Note: either example above could be more detailed or less detailed and still be effective. If you are misaligned with your audience and missing desired results or experiencing procrastination or delays consider where you could be more SMART.

Source

Doran, G. T. (1981). There's a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management's Goals and Objectives. Management Review, 70, 35-36.

Aligning on Expectations: Berkeley’s Expectations Formula

Expectations are what you want to happen or are anticipating will happen. Undefined and unvoiced expectations often lead to misalignment. Use Berkeley’s expectations formula to align with your team members.

Expectations are what you want or are anticipating. They are defined by your perceptions and assumptions. Whoever you are working with has their own set of expectations. Undefined and unvoiced expectations often lead to misalignment. Use Berkeley’s expectations formula to align with your team members.

Tool Summary

This expectations formula helps you to align and clarify the details of your expectations and consider all the various categories where expectations come into play.

How to Apply

To apply this, start by reviewing the categories of expectations.

Role Expectations

What are your various expectations around your team members' roles- their ongoing responsibilities and measures of success:

What are you expecting them to do? Consider their Job Description.

What does it look like if they are successful in that work? What are key performance indicators or other measurements of success?

Who do they work with to accomplish that work?

How do you expect them to prioritize their work?

Project Expectations

Next, what are your various expectations of any project work? These are the one-off tasks or items. What changes from the general role expectations above?

Cultural Expectations

Lastly consider culture as a category. The actions and behaviors of your team become the culture of the team. What are your expectations regarding how you work together- the customs, norms, behaviors, and unspoken rules of working as a part of your team?

It can be helpful to consider how team members you perceive as a great culture fit, act, and behave. What do they do and what don’t they do? How do they work with others? Use examples of their actions and behaviors to codify and communicate expectations around behavior that is in alignment with the culture you want to see.

Considering these three categories of expectations and you can begin to map out your expectations, making them detailed and clear. For each expectation, break it down into the actions, behaviors, and results:

Actions: What you or someone else is expected to do.

Behaviors: How you or someone else will do the work.

Results: What the result is after the work is completed.

Example

Role:

Simplified version: Book 25 demos monthly to hit targets.

Detailed version to clarify expectations: Your primary role responsibility is to book 25 new demos a month by engaging with new inbound leads via email, LinkedIn, and cold calling.

Action- engaging with new inbound leads

Behavior- via email, LinkedIn, and cold calling

Result- to book 25 new demos a month

Project:

Simplified: Participate in the customer research project.

Detailed version to clarify expectations: In collaboration with marketing on our customer research project, you will be a part of 5 interviews in the next month where you will share more about our target customers’ needs to help marketing build new customer profiles.

Action- be a part of 5 interviews in the next month

Behavior- where you will share more about our target customers’ needs

Result- to help marketing build new customer profiles

Cultural:

Simplified: Collaborate with marketing.

Detailed version to clarify expectations: We can only be successful in sales if we work collaboratively with the other teams by sharing our unique knowledge of our customers to ensure a high quality of inbound marketing leads.

Action- work collaboratively with the other teams

Behavior- sharing our unique knowledge of our customers

Result-ensure a high quality of inbound marketing leads

Any of these examples could be more or less detailed. The question is how much detail do you need to share to align on expectations with your audience and achieve desired results.

Measuring Results

When you are practicing a more strategic framing and communication of expectations you should see greater alignment and clarity in your team. You should not find yourself saying “that is not what I thought you were doing.” You all should be able to move faster and ask fewer questions.

Source

Berkely , P. & C. (2022). Performance expectations = results + actions & behaviors. Performance Expectations = Results + Actions & Behaviors | People & Culture. from https://hr.berkeley.edu/hr-network/central-guide-managing-hr/managing-hr/managing-successfully/performance-management/planning/expectations

Delivering Feedback for Success: SBI

Center for Creative Leadership’s feedback tool SBI is a simple formula to share the information your team members need to know how to be successful.

Center for Creative Leadership’s feedback tool SBI is a simple formula to share the information your team members need to know how to be successful.

Tool Summary

SBI is one of the original feedback delivery tools created by the Center for Creative Leadership. Today, there are many more feedback tools to choose from but this is one of the most simple and tested. SBI stands for Situation, Behavior, and Impact. The intention of communicating feedback in this way is to ensure the feedback is clear and objective by adding specificity and removing subjectivity and judgment. The tool advises that you state the situation, define the behavior, and communicate the impact. To round out the formula and make the tool more actionable, add “share your ask” as a fourth step or element - SBI+A.

Adding a suggestion of how to change the behavior or what to do differently can make the feedback feel more motivating as you are providing a solution, not just critique. You can use this formula whether you are delivering feedback, asking for feedback, communicating about feedback in general, or advocating for yourself.

How to Apply

When delivering feedback, you need to communicate enough detail or information so your audience knows how to be successful or knows what behavior to change or reinforce. You need to aim to remove emotion and subjective judgment.

“Great job” and “we need to do better next time” are rarely effective unless timed perfectly because statements like this are not specific enough to let the audience know what to continue doing or what to change.

Use SBI+A to make sure your feedback is detailed, objective, and motivating.

S is for Situation

Situation is the detail- it clarifies the context of the feedback. Defining the situation can often seem easy, but is in fact more challenging than expected. Easy situations may look like, “in yesterday’s meeting…”

When you hear feedback from a third party, you may not know the situation. This is when things become more challenging. As an example, your team member says: “Joe has been challenging to work with, can you address that, [manager]?” You will need to clarify the situation either with the complaining party or with your team member. “Can you tell me more about your recent work with Joe, what’s been happening, how’s it been going?”

B is for Behavior

Behavior is often the most difficult to verbalize and communicate. You need to be objective in your observation The subsequent communication of the behavior needs to be clear and as much as possible, stating facts not assumptions or interpretations. A fly on the wall or a hidden camera should agree with how you describe the behavior. There is no space for subjectivity. For example, consider the difference between “When you state the problem without communicating solutions” vs. “When you complain in our 1:1s.”

You need the person receiving the feedback to agree with your observation of the behavior and then to quickly move on to focus on the change or action (the action can be reinforcement). The more objectively observable the communicated behavior is, the easier it is to avoid getting caught up in confusion, conflict, and emotional reactions and move on to focus on the change or desired action.

I is for Impact

Impact describes the consequence of behavior. It is the motivator behind why your feedback is important to communicate in the first place. The observable impact of a behavior should be significant enough to motivate taking action and achieving results.